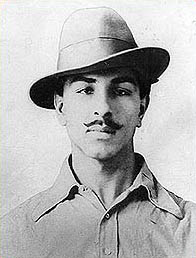

Bhagat Singh was an outstanding figure in the struggle for Indian independence, and paid dearly for his ideals by being hanged by the British colonialists of the time. Attempts have been made to distort what he really stood for, but what is clear from some of his writings is that he rejected the idea of two-stage revolution and saw the workers and peasants as the only truly revolutionary forces upon which the revolution could be based.

We have heard time and time again that the capitalist ruling classes, and their regimes, have deliberately suppressed the revolutionary essence of Bhagat Singh’s ideas. This is undoubtedly true. But this is only half of the whole truth. The other half is that the parties of the Stalinist Comintern, and the elements related to them, have also contributed greatly to this suppression. In both cases the suppression is premeditated and benefits the perpetrators. While the capitalists project Bhagat Singh and his ideas in the grey shades of nationalist patriotism, the Stalinist leadership portrays Singh as a revolutionary sympathetic to the “two-stage” revolution, the Soviet Union, and their caricature of Lenin. Stalinists, and their more recent adherents, the Maoists, attempt to assimilate the ideas of Bhagat Singh with their own.

Did Bhagat Singh belong to the mainstream socialist movement of his time? If so, what was the need for him to remain outside the main current of socialism, which embodied itself in the organisation of the Communist Party of India (CPI)? Why did this party of the Stalinist Comintern fail to impress one of the most ardent revolutionaries of its time? Why did the vibrant generation of youth, treading the suicidal path of terrorism and futile political idealism, reject its appeal? These questions comprise the core of political differences which existed between revolutionary Marxism on the one hand and its Stalinist degeneration, the reincarnation of Menshevism, on the other.

The thoughts and writings of Bhagat Singh throw sufficient light on the failure of contemporary communists to influence more of the younger generations. Acting under the pernicious influence of the Comintern, the CPI leadership utterly failed to put forth a consistent revolutionary policy. Under the direct command of Stalinists since the mid 1920s, its leadership convinced itself more and more that the liberation struggle was being fought as part of the bourgeois democratic stage of the revolution. The whole focus thus remained implemented towards impressing the national bourgeoisie, and pushing them more towards the left, instead of fighting against them for power. In their view the bourgeoisie was the natural ally and leader of the revolution. They viewed the Indian National Congress as the real edifice of political purpose between Marxists and national capitalists.

Singh was strongly opposed to this bogus theory propounded by the Stalinists. He did not have any illusions in the ability of the national capitalists. Singh clearly stated there was no difference between the rule of local or foreign capitalists. For him, it didn’t matter what country the ruling class came from. Colonialism and imperialism were not merely the rule of foreign capitalists to which all social classes of the subjugated nation are equally hostile to, as was preached by the Stalinists, but were the direct rule of world capitalists as a whole upon the working masses of all nations. In his writings, Singh was direct in his rejection of class collaboration. He wrote the following in “Outlines of a Revolutionary Programme: A Letter to Young Political Activists.”

“If you are planning to approach the workers and peasants for active participation, then I would like to tell you that they cannot be fooled through some sort of sentimental rhetoric. They will clearly ask you what your revolution would give them, for which you are demanding sacrifice from them. If in place of Lord Reeding, Sir Purushottam Dass Thakur becomes the representative of the government, how would people be affected by this? How would a peasant be affected if Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru comes in place of Lord Irwin? The appeal to nationalist sentiments is a farce. You can not use them for your work.”

When Stalin was telling his followers in India to associate themselves with Gandhi and Congress, Bhagat Singh was exposing the false preachings of Gandhi through his writings in newspapers and leaflets. Singh wrote:

“He (Gandhi) knew from the very beginning that his movement would end into some sort of compromise. We hate this lack of commitment…”

He wrote further about Congress:

“What is the motive of Congress? I said that the present movement will end in some sort of compromise or total failure. I have said so because in my opinion the real revolutionary forces have not been invited to join the movement. This movement is being conducted only on the basis of a few middle class shopkeepers and a few capitalists. Both of these classes, specifically the capitalists, cannot venture to endanger their property. The real armies of the revolution are in villages and factories ‑ the peasants and workers. But our bourgeois leaders don’t dare take them along, nor can they do so. These sleeping tigers, once they wake up from their slumber, are not going to stop even after the accomplishment of the mission of our leaders.”

Singh’s words found their endorsement when after the Bombay action of weavers, Gandhi, the leader of the national bourgeoisie, expressed fear of the revolutionary class by saying that the “…use of the proletariat for political purpose is extremely dangerous”.

Amazingly, when Leon Trotsky was offering his severe criticism of Stalinist policy in India, Singh was making a similar critique of the false leadership of Gandhi and the Indian National Congress. It is not without reason that Singh, at the time unaware of Trotsky’s thoughts, was himself thinking along the same lines. He refused to collaborate with the Menshevik programme of conciliation with national capitalists and remained consistent on this political position his entire life. Rather than follow the CPI, Singh drew his inspiration from the action and programme of the Gadar party.

Bhagat Singh was thoroughly convinced of the complete reactionary character of the national capitalists. He did not subscribe to the views of the CPI. He had no desire to fight “alongside the capitalists” in the first stage and “against the capitalists” in the second. To Singh, the revolution was a socialist revolution in which the power must fall to the hands of the working class, with the peasantry as its ally. He never dreamt of a bourgeois republic, and never allowed the possibility of sharing power between the workers and peasants on one side and capitalists on the other.

Singh was also a staunch opponent of the “non-violence” preached by Gandhi. Gandhi’s doctrine, which was nothing but a trap to hold back workers and peasants from taking the offensive against the property and rule of capitalists, was at direct odds with what he advocated. Singh wrote this on Gandhi:

“It was the principles of non-violence and compromising policy of Gandhi which created a breach in the united waves that arose at the time of the national movement.”

Singh brought forward vivid explanations enriching the revolutionary theory and experience of his time. He supported, and justified, the use of revolutionary violence by the revolutionary classes against the reactionary ones. His writings were a befitting reply to the docile, meek, and virtually servile positions of Gandhi and his followers inside the Congress.

The perspective of Bhagat Singh was, however, limited by various factors, including his very young age, extremely short life span, the politically undeveloped environment, the destructive anti-revolutionism of the Stalinist leadership, etc. But even within these limits, his influences were clear. Although Stalinism built a wall to block the revolutionary wave created by the October Revolution, the lessons of Russia still got to India and exerted immense influence upon a young Bhagat Singh. (Towards the end of his life it is known he was going through the works of Lenin and Trotsky.) Singh was also no doubt influenced by the sacrifice of Kartar Singh Sarabha, the organiser of the Gadar Party in the U.S. Sarabha used political propaganda to penetrate the armed forces and planned to cause a revolt to uproot the colonial regime, but was imprisoned at the age of 19 on charges of sedition and waging war against the empire.

Singh also spent time in jail. It was during this time, as his life was nearing its end, he made perhaps his greatest contribution to the revolutionary cause. He smuggled out of his cell a programme for revolution in India. In this he consciously rejected the path of individual terrorism and vowed for the organisation of a mass uprising of workers and toilers against imperialism. While acknowledging armed struggle as a valid, legitimate, and probable possibility in the revolutionary struggle, Singh rejected terrorist methods of struggle as both futile and harmful.

At the young age of 23, Bhagat Singh was hanged by the colonialists. They had the tacit support of the Gandhi-led bourgeois leadership in Congress. This is evident not only by the mysterious silence of these leaders on the issue, but also because of the fact that Gandhi categorically refused to make the sentence of Singh an issue at the round table conference.

Although Singh was not aware of the political disputes between Trotsky and the conservative Stalinist bureaucracy, he deduced the same political conclusions Trotsky arrived at while fighting for a re-orientation of the world communist movement. This is all the more remarkable considering he did not live to see the total revolutionary betrayal by the Stalinists when they took sides with British colonialists and abandoned the freedom struggle completely.

In their own way, capitalists and Stalinists both contributed to obliterating the revolutionary ideas of Bhagat Singh. They purposely have sought to intermingle his earlier radical reflections, which stand mixed with nationalist prejudices and idealist beliefs prevalent in his time, with later drawn conclusions. The duty of revolutionaries is to segregate the politically mature Singh from the earlier more ideal driven one, and to put his works and thoughts in context. Even today Bhagat Singh can educate and attract people across the world towards a true revolutionary programme.