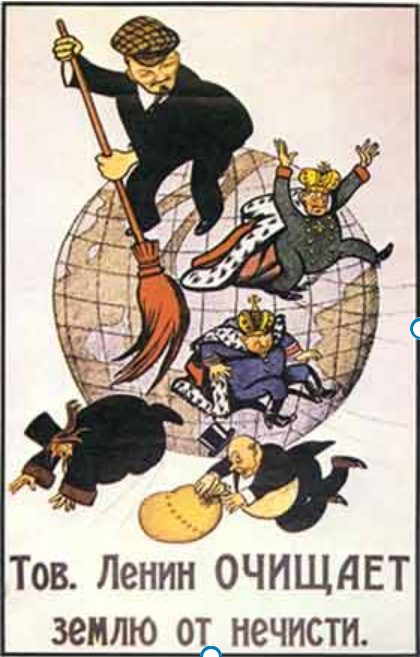

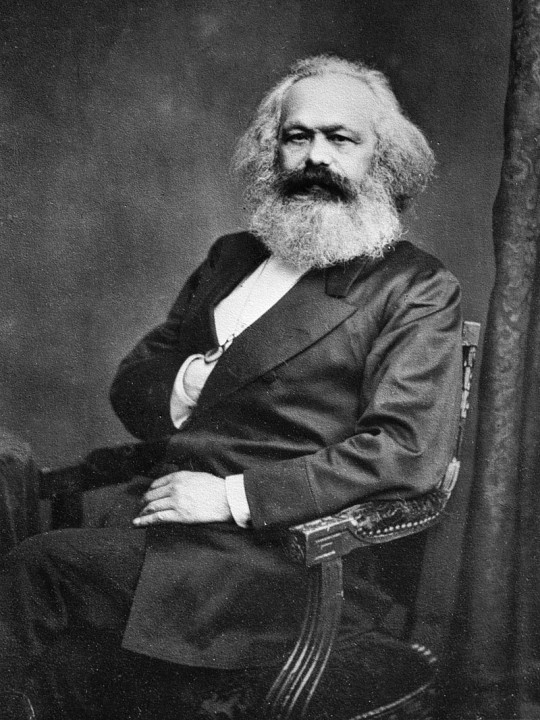

There has never been a better or more important time to publish Marx’s classic pamphlet on the lessons of the Paris Commune, The Civil War in France. Today, 150 years since the birth of the Commune, millions of workers are rising up against the injustice and inhumanity of the capitalist system. In such a period of momentous class struggle it is vital that the working class should know and understand its own history.

The Civil War in France is a series of addresses from the General Council of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA), drafted by Marx, starting in July 1870 with the onset of the Franco-Prussian War and ending in May 1871 with his defence of the Paris Commune, which was at that very moment being violently crushed. It is a masterful application of the Marxist method to the questions of war, revolution and the state and should be compulsory reading for any socialist.

However, the fact that Marx’s addresses were drafted and delivered in the heat of the events themselves meant that much of the historical background and the specific events of the Commune were left out. It is therefore the intention of this introduction to provide some of that detail, along with insights provided in Marx’s letters of the time, so that the modern reader can get as much out of this classic text as possible.

This text is an introduction to Wellred Books’ new republication of The Civil War in France by Karl Marx, which is now available to puchase.

The rise and fall of the Second Empire

France is often considered the archetypal ‘republican’ country, but this was by no means the case 150 years ago. In fact, the people of France spent the majority of the nineteenth century living under the rule of three kings and two Bonapartes.

In February 1848, the masses, and the Parisian proletariat in particular, rose up and overthrew the “bourgeois monarchy”[1] of King Louis Philippe I. But having won the Republic the workers did not limit themselves to only democratic demands. As with the British Chartists of the same period, beneath the workers’ democratic aspirations lay social, class demands: the desire for a new social order with the republic as a means to achieve it. On the other hand, no section of society was more opposed to the democratic republic than the big bourgeoisie, which rallied behind the two rival monarchist factions, the ‘Legitimist’ supporters of the old Bourbon dynasty and the ‘Orleanist’ defenders of Louis Philippe. This contradiction at the heart of the republic would produce an intense and bitter struggle, which would leave its mark on the events of 1870-71.

The new republic of 1848 announced its birth with a massacre of the most radical Parisian workers in June of that year. But even that wasn’t enough to satisfy the ruling class. After less than four years, the republic was dissolved by a military coup on 2 December 1851, carried out by its own president, Louis Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. After four years of storm and strife, the landlords, industrialists and financial swindlers were clamouring for ‘Order’ above all and were more than prepared to sacrifice the bourgeois republic in return for peace and profits. As Marx explained in his classic work on the birth of the Second Empire, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

Thus… the bourgeoisie confesses that its own interests dictate that it should be delivered from the danger of its own rule; that, in order to restore tranquillity in the country, its bourgeois parliament must, first of all, be laid to rest; that, in order to preserve its social power intact, its political power must be broken…[2]

With the blood of thousands of workers the bourgeoisie had bought itself eighteen years of social peace under Bonaparte. But even in this period of reaction, the mole of revolution was burrowing away. The capitalist upswing that followed the establishment of the Second Empire inevitably strengthened the ranks of the working class and as a new generation of workers began to strain against the Bonapartist yoke, they turned to revolutionary ideas, including those of the IWMA, which in France contained both Proudhonist (a form of anarchism) and what we would today call Marxist tendencies.

In 1869 the workers began to move again and the Empire, ostensibly so powerful with its gigantic army, police and bureaucracy, found itself suspended above a seething cauldron. Confronted with the same choice as all doomed regimes, that of repression or concessions, the government first attempted to repress the workers and then to appease them. Both only emboldened the masses. Elections were called for May 1869, offering the choice between the regime and a tame opposition. The government only received fifty five per cent of the vote, concentrated overwhelmingly in the most backward, rural parts of the country. The opposition more than doubled its votes and Paris overwhelmingly elected Republican candidates.

Sensing weakness, the workers went on the offensive. Crowds assembled in Paris, singing the hymn of the Great French Revolution, La Marseillaise. After the cousin of the Emperor shot and killed a journalist, Victor Noir, in January 1870, the Parisian masses responded with an enormous demonstration, numbering 200,000. The authority of the Emperor was in tatters. Forced to offer the spectre of reform in order to prepare the jackboot of reaction, Bonaparte called a plebiscite, effectively a vote of confidence, in which voters were asked to endorse the regime’s ‘liberal’ reforms, or reject them. At the same time, known members of the IWMA were arrested in order to limit their growing influence amongst the working class.

On the face of it the May 1870 plebiscite gave Bonaparte a resounding victory, with 82.7 per cent of the vote going in his favour. As in 1869, the regime had relied on the support of the rural masses, while Paris overwhelmingly voted ‘no’ or abstained. But amidst the celebrations in the Tuileries Palace and the Paris stock exchange, the outline of the future crisis could still be seen. Only four months later, the Second Empire was no more.

Not for the first nor the last time in history, national chauvinism and war were turned to as a means of rallying support around the state. Bonaparte hoped that by hurling France into a war with Prussia for the domination of Europe he would exorcise the ghost of 1848, which was looming over the nation. As Marx notes: “The war plot of [19] July 1870 is but an amended edition of the coup d’état of December 1851.”[3] But it was precisely this adventure which would finish off the Empire for good.

The French Emperor declared war on 19 July 1870. Both sides rapidly mobilised hundreds of thousands of troops and threw them into the pointless carnage. Overstretched and outmanoeuvred, the French armies suffered a series of bloody defeats. On 18 August, the French Army of the Rhine under General Bazaine retreated to Metz, which was besieged by the Prussians.

Bonaparte’s project of invading Germany was hopeless, and yet his generals continued to throw themselves into the traps laid for them. In reality, they preferred the prospect of defeat to a foreign enemy over revolution at home. An eye-witness of the Commune, Lissagaray, writes in his History of the Paris Commune of 1871 that the Bonapartist Minister, Palikao, had written to the head of the French forces, Marshall MacMahon on 27 August, stating: “If you abandon Bazaine we shall have the Revolution in Paris.”[4] The Emperor led the army himself in an attempt to rescue Bazaine. On 1 September 1870, he was caught at Sedan, surrounded by 200,000 Prussian troops. After losing over 17,000 of his men trying to break out of Prussian encirclement, Bonaparte surrendered to the Prussian leader, Bismarck, on 2 September, along with the whole of his army.

At the news of the defeat at Sedan and the Emperor’s capture, the ruling class began conspiring to replace the Empire with a constitutional monarchy. The bourgeois republicans on the other hand could think of nothing other than the maintenance of order. In response to Parisian demonstrators demanding a republic, the ‘radical’ Leon Gambetta announced: “You are wrong; we must remain united; make no revolution.”[5] But his pleas fell on deaf ears. On the morning of 4 September, the workers assembled in their National Guard battalions (a militia first organised in 1789 for policing and military reserve purposes), forced their way into the Corps Legislatif, cleared the deputies of the now defunct assembly out of the hall and forced the same Gambetta to declare the abolition of the Empire.

At the Hôtel de Ville (city hall), the Parisian deputies proclaimed a new republic and announced themselves as the new “Government of National Defence” under pressure from the masses. Thus the Third French Republic was born: a bourgeois democratic revolution carried out in defiance of the bourgeoisie itself. With one push the workers had established the Republic, but entrusted its defence to “a cabal of place-hunting barristers”,[6] whose mandate consisted in nothing more than the fact they represented Paris in a Bonapartist parliament.

The siege of Paris

It may be asked why, having toppled the Empire by their own strength, the workers allowed themselves to be duped by such a hypocritical and useless “cabal” as the likes of Gambetta, even applauding the names as they were read out at the Hôtel de Ville. This may seem all the more puzzling when one considers the revolutionary events that were to come. But what this apparent contradiction demonstrates is precisely the contradictory nature of consciousness itself. As Trotsky explains in his masterpiece, The History of the Russian Revolution, “The swift changes of mass views and moods in an epoch of revolution thus derive, not from the flexibility and mobility of man’s mind, but just the opposite, from its deep conservatism.”[7] The masses will only take the dangerous path of revolution when the impossibility of continuing with the present situation becomes an undeniable fact, but even then they do not necessarily rise up with a clear plan of the way forward.

The Russian masses rose up in February (March in our calendar) 1917, and toppled the centuries-old despotism of the Tsar in a matter of days. Their power was irresistible. And yet power fell into the lap of a ‘Provisional Government’, a cabal perhaps even more motley than the Government of National Defence in 1870. In Russia, as in France, the workers although triumphant, naturally assumed that power should go to their ‘superiors’: the famous men of politics who had represented them in the past. After all, this view is reinforced by decades of experience in all countries in normal times. But the masses do not give their leaders a blank cheque; painful experience teaches the masses to know their own strength as they test and discard those leaders and parties who obstruct their path.

The Paris workers cheered the Government of National Defence because they saw in it the only available means to repel the Prussians. Even the most hardened revolutionaries became intoxicated by this mood of ‘national defence’. The local section of the IWMA sent delegates to the Hôtel de Ville, offering their support in the organisation of the defence. Auguste Serraillier, an Internationalist worker in Paris wrote to Marx, outraged at this capitulation to the “ultra-chauvinist” mood, explaining: “When I express indignation at their conduct, they tell me that, were they to speak otherwise, they would be sent packing!”[8]

An observer at the time, if they only took account of the superficial mood on the surface of society, could have written off the Parisian workers as too ‘co-opted’ by chauvinist illusions to carry out a revolution, as many ‘left-wing’ commentators do today. And yet it was the same workers who little more than six months later elected foreigners to the Commune, declaring that “the flag of the Commune is the flag of the World Republic”,[9] and who cheered as they pulled down the Vendôme column (a monument dedicated to Napoleon’s conquests). On the basis of events, the illusions of the masses would be transformed into their opposite.

https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/1013436325&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true

Marxist Voice · The Paris Commune at 150

For the Parisian worker a predatory war waged by his own oppressor represented nothing but a strengthening of his own oppression in the case of victory, and an intensification of his suffering in the case of defeat. But the capitulation of Bonaparte, the abolition of the Empire, and the intention of Bismarck to transform a war of defence into a war of plunder against the French people changed all this. Albeit in a confused way, intermingled with national chauvinism – which is omnipresent in bourgeois society – the worker saw the continuation of the war as the defence not only of France but of the Republic. And crucially, behind the Republic lay not just a political ideal but the means to realise his own class interests. In short, what the workers were unconsciously striving for was a workers’ republic, which they were prepared to defend against all comers. And they would have to.

Neither Bismarck, nor the French ruling class had any interest whatsoever in preserving the Republic of 4 September 1870. For Bismarck, the presence of a democratic republic on his Western border offered nothing but an example for the oppressed German masses, particularly the workers, who organised demonstrations in Berlin against the continuation of the war and for the recognition of the Republic. For the French capitalists of all shades, a republic with the Paris workers at its head was anathema, just as it had been in 1848. A monarchy along the lines of the British state provided a much better political cover for the class rule of the bourgeoisie in their eyes.

In the meantime, the bourgeois republicans, who had been forced to take up the reins of the state in order to prevent them falling into the hands of the workers, publicly declared they would “not cede an inch of our territory, nor a stone of our fortresses”.[10] The Paris National Guard, which was overwhelmingly proletarian and petty bourgeois (small business owners such as shopkeepers, artisans etc.) in its composition, eagerly answered the call. On 14 September, when General Trochu, a Bonapartist given command of the armies of the Republic, held a review of the National Guard in Paris, 250,000 men assembled. But within days, this Government of National Defence had shown itself to be a “Government of National Defection”,[11] as Marx put it.

Despite having a potential force of 500,000 men at their disposal, armed with hundreds of artillery pieces and superior rifles to those of the enemy, the Government of National Defence squandered every opportunity to repel the Prussian invasion. This was no accident. As Marx explains:

A victory of Paris over the Prussian aggressor would have been a victory of the French workmen over the French capitalist and his state parasites.[12]

This fact was recognised by Trochu himself, who replied to Fevre’s appeals for more serious offensive measures that “would give the upper hand to Parisian demagogy”.[13] Bismarck succeeded in surrounding Paris and began the siege on 20 September 1871.

Meanwhile, in contrast to the paralysis of the government, the Parisian workers had begun to create their own organs for the defence of the city. From 4 September, public assemblies had been taking place in each arrondissement(district) of the city. At the instigation of revolutionary speakers, including those from the IWMA, these assemblies elected a local “Committee of Vigilance”, and sent four delegates each to a “Central Committee of the twenty arrondissements”. This committee, which was largely made up of workers and known revolutionaries, established itself in the headquarters of the IWMA and the Federation of Trade Unions at Place de la Corderie. It was, in effect, the embryo of a workers’ government, similar to the soviets set up by Russian workers in 1905 and again in 1917.

The Central Committee immediately counterposed itself to the National Government. As early as 4 September, the day the government established itself, the Committee issued a manifesto, with the following demands:

[T]he election of the municipalities, the police to be placed in their hands, the election and control of all the magistrates, absolute freedom of the press, public meeting and association, the expropriation of all articles of primary necessity, their distribution by allowance, the arming of all citizens, the sending of commissioners to rouse the provinces.[14]

But these demands, which would eventually be realised in March, did not yet have the support of the wider masses, beyond the vanguard of the working class. Lissagaray writes, “Paris was then infected with a fit of confidence. The bourgeois journals denounced the committee as Prussian… Their placards were torn down.”[15]

As the inability of the National Government to break the Prussian siege became increasingly apparent, the idea of resurrecting the Paris Commune of 1792 as a means to save the city began to circulate. The original Commune had essentially been a city council, with representatives elected from the various districts of the city. The reason that the most radical layers looked to the Commune for salvation is that during the Great Revolution of 1789-94 it had been dominated by the most hard-line Jacobins and played a central role in the fall of the Monarchy and the establishment of the Jacobin Convention. It had been suppressed in 1795, after the fall of Robespierre and the installation of the counter-revolutionary Directorate.

The Communards hoped that by handing the running of the city to the people, the Commune would not only ensure a more effective resistance to the siege but would also provide a means to pressurise and even break with the National Government. Their chance came sooner than they thought. On 31 October, the people of Paris awoke to the news that Bazaine had surrendered at Metz along with his entire army, while the Orleanist leader, Adolphe Thiers, had been sent to negotiate an armistice. That afternoon, Paris erupted with demonstrations demanding, “No armistice!”, and, “Down with Trochu!”[16] Just as on 4 September, a crowd stormed the Hôtel de Ville shouting, “Vive la Commune!” Yet again, power hung in the balance.

A member of the Central Committee of the twenty arrondissements swiftly climbed a table and announced the abolition of the government and a commission was appointed to arrange new elections. The troops of the National Guard who were led to the Hôtel de Ville to put down the insurrection raised the butt end of their rifles to indicate they would not fire. Jules Ferry, a member of the National Government recalled that at that moment: “the Parisian population, from highest to lowest, was absolutely hostile to us. Everybody thought we deserved to be dismissed.”[17] And yet by the next day, Ferry, Trochu and the rest of the government were safely back in power.

At that time the mood of the Parisian masses had certainly turned extremely sour in relation to the government, but they had not yet turned to the revolutionaries – figures like Auguste Blanqui – to lead them. As the day went on, the most revolutionary battalions of the National Guard, assuming that victory had already been won, left the Hôtel de Ville without instructions. Meanwhile, more conservative battalions were rallying to Trochu, having been told that a gang of notorious revolutionaries, with Blanqui at their head, had taken the government prisoner. That night, the forces of order succeeded in retaking the Hôtel de Ville and arrested Blanqui, almost without resistance. The first Communard insurrection, premature and unplanned, had failed.

In the municipal elections that followed, the majority of arrondissements elected mayors who supported the Government. The revolutionaries, “wanting in cadres, in method, in organisers”,[18] were sidelined in all but the poorest and most militant districts. Those Communards who had been elected in the 19th and 20th arrondissements could not take their seats as the Government had issued a warrant for their arrest. The most well-known revolutionaries were forced into hiding.

The winter months took a heavy toll on the inhabitants of the besieged city, particularly the poor. Lissagaray paints a harrowing picture of the suffering:

From hour to hour the sting of hunger was increasing, and horse-flesh had become a delicacy. Dogs, cats, and rats were eagerly devoured. The women waited for hours in the cold and mud for a starvation allowance. For bread they got black grout, that tortured the stomach. Children died on their mothers’ empty breasts. Wood was worth its weight in gold, and the poor had only to warm them the despatches of Gambetta, always announcing fantastic successes. At the end of December their privations began to open the eyes of the people. Were they to give in, their arms intact?[19]

On 6 January, the Republican Central Committee of the twenty arrondissements met to discuss how to respond to the dire situation. They issued a statement denouncing the treacherous role of the government in the strongest terms:

To the people of Paris, The delegates of the Twenty districts of Paris. Has the government which on 4 September took on the task of national defence carried out its mission? No![20]

After a detailed explanation of the failure of the government in conducting the war, came the conclusion:

If the men at l’Hôtel de Ville still have some patriotism left inside of them then their duty is to step down and to let the people of Paris take charge of their own deliverance.

An alternative program of action was outlined:

The population of Paris will never accept this shame and misery. They know that there is still time, that decisive measures will allow for workers to live and for everyone to join the battle. GENERAL REQUISITION – FREE RATIONS – MASSIVE ATTACK

The insurrectionary statement ended with a rallying cry: “make way for the people, make way for the Commune”. The statement, in red paper and signed by 140 delegates, was pasted on the walls of Paris in the early hours of 7 January. The Red Poster did not yet lead to the actual declaration of the Commune, but clearly foreshadowed the events of 18 March.

Eventually, hoping they had succeeded in starving the republican workers into submission, the Government of National Defence achieved what it had always sought to do. On 27 January 1871, Jules Favre surrendered Paris to Bismark on the condition that the forts were disarmed, Paris was to pay 200 million francs in two weeks and an assembly was to be elected to conduct peace negotiations as soon as possible. The war with Prussia was coming to an end; the civil war was about to begin.

Dual power

Under Bismarck’s direction, France went to the polls on 8 February. The result of these first legislative elections held under the Third Republic was a big majority for the two monarchist parties, who, despite disagreeing over which monarch was to rule them, had formed a united front of reaction with the clergy. Skilfully using the demand for peace at all costs, the Monarchists won 62 per cent of the vote, overwhelmingly amongst the peasantry, and 396 out 638 seats. The republicans found themselves in a minority in their own republic but in the majority in the towns. Paris voted overwhelmingly for the republican candidates, with the future leader of the Commune, Louis Delescluze, receiving 154,000 votes. The class split in the country could not have been laid out more starkly. This split, expressed geographically in the opposition between the Legislative Assembly in Bordeaux and republican Paris, would soon explode into civil war.

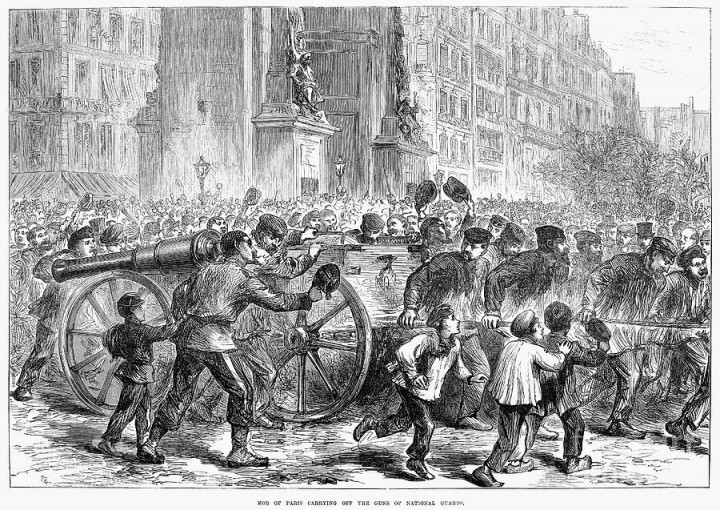

The National Guard, the armed people, became the de facto power in Paris, and the National Guard answered only to its elected committees and to the Central Committee at its head / Image: public domain

The workers’ fears for the future of the Republic, and their own, were completely confirmed by the alliance of “pig-tailed nobles, well-to-do farmers, captains of industry”[21] who formed the so-called ‘Rurals’ in the Assembly. Thiers, the head of the Orleanists (the largest monarchist faction), became the head of the government, while republican speeches in the assembly were drowned out by howls of “Vive le Roi!”[22] (long live the King). Republican newspapers were suppressed. The Assembly even passed a resolution stating that Paris should no longer be the capital of the country, which should instead be at Versailles. Thiers placed the National Guard, still under arms, under the command of the Bonapartist general, D’Aurelles. The proletarian National Guard was to be disarmed, by force if necessary – a massacre along the lines of June 1848 was clearly being prepared.

As has often happened in history, the whip of counter-revolution served to push the revolution forward. The naked threats of the Rurals only hardened the determination of the workers and served to rally the radicals sections of the urban petty bourgeoisie around them. The National Guard in Paris, which was nothing other than the armed workers and petty bourgeois masses, resolved to form a confederation out of its battalions, led by a Central Committee elected from its ranks. On 24 February, 2,000 delegates assembled to elect their leadership. Eugene Varlin, a member of the IWMA, proposed the following resolutions: that the National Guard only recognises leaders elected by itself, and that the National Guard protests “against any attempt at disarmament, and declares that in case of need it will offer armed resistance”.[23] Both were passed unanimously.

There were now, in effect, two powers existing side-by-side in France by this time. The Assembly at Versaille, which had concluded peace with the Prussians on 26 February in return for the region of Alsace-Lorraine and reparations of 5 billion francs, continued to rage against Paris. The Rurals proposed to stop the pay of the National Guardsmen and end all debt-relief for the poor, but their commandments were largely ignored. The National Guard held armed demonstrations with impunity. On 3 March, the Minister of the Interior, Picard, called on “all good citizens to stifle these culpable demonstrations”,[24] but no one answered the call. Deprived of legal publications, the revolutionaries plastered the city with posters, which were read avidly and protected by the masses.

The National Guard, the armed people, was now the de facto power in Paris, and the National Guard answered only to its elected committees and to the Central Committee at its head. Such a situation of dual power cannot go on indefinitely. No nation can have effectively two states led by two different classes at the same time; one must conquer the other. Either the ‘Versaillais’ (the forces of the national government based in Versailles) would crush Paris or Parisian workers would crush Versailles. Out of this conflict was born the Commune.

The birth of the Commune

The workers of Paris effectively held power in their hands but did not know what to do with it. They had not yet resolved to break conclusively with Versailles, but nor did they have any intention of relinquishing their arms. Meanwhile, Thiers was preparing to strike what he hoped would be a decisive blow. He appointed another Bonapartist general, Vinoy, to prepare a force capable of disarming Paris. The problem was that no such force existed.

The capture of so much of the regular army by the Prussians, along with the general level of demoralisation, had left Vinoy with no more than 25,000 troops, already “on the point of mutinying”.[25] With such a force he could only attempt to disarm the National Guard under cover of darkness, like a thief in the night. In the early hours of 18 March he made his move.

From three o’clock in the morning, several columns marched to strategic points throughout the city with the aim of securing and carrying off the cannon which had been in the possession of the National Guard since the siege. They reached their targets almost without resistance. At the Tower of Solferino the invaders were stopped by a single sentry, who was cut down, the first casualty of the civil war. The Versaillais believed themselves victorious. Posters were immediately put up announcing the coup:

Inhabitants of Paris, in your interest the Government has resolved to act. Let the good citizens separate from the bad ones; let them aid public force; they will render a service to the Republic herself… The culpable shall be surrendered to justice. Order, complete, immediate and unalterable, must be re-established.[26]

Unfortunately for them, in one of the tiny but momentous accidents that punctuate history, they had forgotten to bring any horses to carry the cannon away with. For several hours the champions of order waited for their horses to arrive, while the Parisian proletariat was beginning to stir.

The first to rise were the women. At the sight of the soldiers the working women of Paris crowded around, scolding the troops: “This is shameful; what are you doing there?”[27] The regular troops stood in silence while their officers tried in vain to disperse the crowd. Eventually, at the women’s summons, the National Guard assembled and began to march up to the heights where the cannon was stationed. Fraternising with the regular troops they were allowed to pass. At Montmartre the commanding officer, Lecomte, ordered his troops to fire. The crowd advanced but the troops did not shoot. He ordered them to fire again, and again, but at the third order his troops turned and arrested him instead. This scene was repeated at every point. Everywhere the troops fraternised and joined the revolution. By 11 o’clock the people were back in complete control of the city and the forces of ‘Order’ were in full flight.

The architects of the coup were beside themselves with panic. The government had been following events at the Foreign Ministry in Paris. At the first reversals, its courageous chief, Thiers, immediately ordered the evacuation of Paris and fled down the back stairs. But while Thiers was scampering out of the city, the Central Committee of the National Guard, the de facto government, had still not fully grasped what was happening. Far from planning the insurrection, they had not even planned for Thiers’ coup, as the absence of sentries on the night of the 17th attests. Only at two o’clock, three hours after the coup had been overturned, did the leaders of the revolution transmit orders to occupying official posts, such as the Hôtel de Ville. They didn’t so much seize power; power seized them.

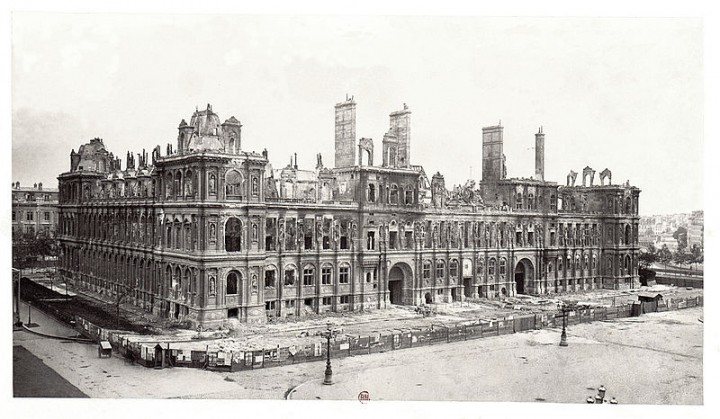

The National Guard proceeded to take control of the national printworks and the Napoleon barracks. They were met with next to no resistance. At half past seven, over eight hours since Thiers had fled, the Hôtel de Ville was surrounded and occupied. The mayor, Jules Ferry, abandoned by his men and without a word from the now fugitive government, avoided capture by jumping out of a window. Presumably he feared the National Guard might do to him what he had been planning to do to them.

Far from seeking reprisals or hostages however, the Central Committee could scarcely even reconcile itself with the idea that it was now in charge. They debated and deliberated while the remaining forces loyal to the Assembly trickled in complete disarray through the open gates of the city. Marx lamented this missed opportunity, writing in a letter dated 12 April 1871:

If they are defeated only their ‘decency’ will be to blame. They should have marched at once on Versailles, after first Vinoy and then the reactionary section of the Paris National Guard had themselves retired from the battlefield. The right moment was missed because of conscientious scruples. They did not want to start the civil war, as if that MISCHIEVOUS avorton [little runt] Thiers had not already started the civil war with his attempt to disarm Paris![28]

In spite of this criticism however, he still expressed his admiration of “these Parisian, storming the heavens”.

The only reprisals taken against the leaders of the coup were the executions of the generals Clément-Thomas and Lecomte, the same individual who hours earlier had thrice ordered his troops to fire on a crowd including unarmed women. But even this act of revenge was carried out by their own troops in defiance of the representatives of the Central Committee, who called for a court martial. The remaining captives were all set at liberty. On this day, 18 March, which the ruling class had intended to be a bloodbath, the working class took power into its hand with a tiny number of casualties, with no damage to property or looting and in a state of almost complete calm. As ever, threatened with destruction, the working class demonstrated its magnanimous humanity – if anything to a fault – in contrast to the raving brigands of ‘Order’.

Next came the question of power: what to do with it? The Central Committee was split. Some advocated a march on Versailles, the overthrow of the Legislative Assembly and an appeal to the provinces. Others protested, “We have only the mandate to secure the rights of Paris. If the provinces share our views, let them imitate our example.”[29]

Here, the absence of a revolutionary party was acutely felt. The leadership of the revolution, although overwhelmingly proletarian, was more a collection of individuals thrown together by events than a party with a common strategy. The closest thing to a party of the working class, the IWMA, was not united by a common programme and discipline, with a centralised leadership. Most of the members of the Central Committee had neither expected nor desired to seize power. Perhaps remembering the failed insurrection of 31 October, their first thought was to hand it over as quickly as possible. While the remnants of Vinoy’s army were escaping, the Committee absorbed itself in the organisation of elections.

The next morning, the people awoke to find the red flag flying over the Hôtel de Ville and the following proclamation on the streets:

Citizens, the people of Paris, calm and impassable in their strength, have awaited without fear, as without provocation, the shameless fools who want to touch our Republic. Let Paris and France together lay the foundation of a true Republic, the only Government which will forever close the era of revolutions. The people of Paris is convoked to make its elections.[30]

Thus began the Paris Commune.

What was the Commune?

After some delay and hesitation, the communal elections took place on 26 March. A total of 70 seats on the ruling Council of the Commune were elected on the basis of universal male suffrage, subject also to the right of recall. The maximum salary of any official of the Commune, including its Council members, was 6,000 francs, eliminating the privileges of office and careerism which infest our own ‘democracy’. On the 28th the Commune was proclaimed to an enormous assembly of 200,000 people, who greeted the proclamation with chants of “Vive la Commune!” and singing La Marseillaise.

The Commune had become a reality, but even amongst the Communards themselves this meant different things. As Lenin once remarked, “Whoever expects a ‘pure’ social revolution will never live to see it.”[31] For some the Commune was merely a municipal body, the purpose of which was to guarantee Paris’ administrative autonomy under the Republic. At the first sitting of the Council, which proclaimed the Commune on 28 March, the presiding member by seniority of age, a capitalist by the name of Beslay, gave the following opening speech:

The Republic of 1793 was a soldier, who wanted to centralise all the forces of the nation; the Republic of 1871 is a workman, who above all wants liberty to fecundate peace. The Commune will occupy itself with all that is local, the Department with what is regional, the Government with what is national. Let us not overstep this limit, and the country and the Government will be happy and proud to applaud this revolution.[32]

The more radical and proletarian elements on the other hand saw it as something much more: the means by which they could achieve their social as well as political emancipation. And despite the contradictions and confusion at the top of the movement, it was this revolutionary, proletarian side of the Commune that broke through.

The true class nature of the Paris Commune was revealed not in any manifesto or speech, but in practice. The working masses had given birth to the Commune, and even before it had officially been proclaimed they set about shaping it. Churches were packed with people who came to listen to fiery revolutionary speeches delivered from the pulpit, draped in red, and to discuss the events of the day. Resolutions were drawn up and passed on the spot to be submitted to the Central Committee at the Hôtel de Ville. The workers felt their own power and they were learning how to use it.

The first act of the Commune was to dissolve the standing army and make the National Guard the only military force, replacing the “special bodies of armed men” of the state with the armed people. This was a fundamental break from even the most revolutionary movements of the past, as Marx noted in The Civil War in France. In reality the Commune represented a fundamentally new form of state. Lenin, writing in the midst of the Russian Revolution of 1917, described the democratic measures of the Commune described above as “a bridge leading from capitalism to socialism”.[33] He even based his conclusions about how a workers’ state should be organised after the seizure of power on the institutions of the Commune, in particular the election and right of recall of all public officials, who should serve on a workers’ wage, and the replacement of the standing army for the armed people.

As Marx puts it in The Civil War in France, the Commune was:

[T]he political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labour [which] was therefore to serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundation upon which rests the existence of classes, and therefore of class rule.[34]

The “uprooting of the economical foundation” of society began almost as soon as the Commune came into being. As the Communards began the work of organising and defending the city, they immediately met with the sabotage of the enemy. On their arrival at the Ministry of Finance, the post office, the printworks, the telegraph exchange, at all the administrative centres of the city, the Communards discovered that most of the former officials had fled, along with the seals, registers and cash of the districts. Even the management of the cemeteries had been sabotaged. The new power had to improvise the organisation of everything from taxes, to the post, to the police, to the street lamps. But this need for improvisation also unleashed the creativity of the workers.

The post office, for example, had been completely disorganised. The Communards, without the benefit of highly paid functionaries or advisors, managed to get the service running again in two days and succeeded in smuggling post out of the city through the Versailles blockade. In the printing office, the Commune had the managers appointed by the postal workers themselves, and when administrators from the old regime put obstacles in the way of putting up proclamations, the workers simply organised themselves and completed the work without paying any attention.

The Commune increased the print workers’ salaries by twenty-five per cent, but at the same time saved the printing office 200 francs a day by cutting the exorbitant salaries of the highest officials (who had fled in any event), and cutting the waste caused by the previous bureaucracy. Workers’ control wasn’t just better for the workers; it worked better too. The budget of the printing office leading up to 18 March was 120,000 francs a month. Under the Commune it never reached more than 20,000 francs a week. As Marx comments:

The Commune made that catchword of bourgeois revolutions – cheap government – a reality by destroying the two greatest sources of expenditure: the standing army and state functionarism.[35]

The Department of Labour and Exchange was put under the direction of Leo Frankel, a leading member of the IWMA. Under his leadership, assisted by a commission made up of working men, night-work was suppressed as well as the sale of objects sold to pawn shops. Fines taken from workers’ wages were banned. But this was only the beginning. As Frankel himself wrote, “The establishment of the Commune necessitates institutions protecting the workmen from the exploitation of capital.”[36]

In the few short weeks of the Commune’s existence, elements of socialist planning and control of the economy by the working class were being introduced. Offers and requests for work were registered in each arrondissement with the view of eliminating unemployment. Even more significant, all workshops which had been abandoned by their fleeing owners were to be handed over to the workmen themselves, with commissions appointed by the Trade Union Chambers to inspect the books and inventories. All applications for government contracts had to specify the level of wages in order to prevent a race to the bottom and preference was to be given to the workers’ corporations. Rents were suspended for all, except for the industrialists who had profited from the siege. These measures were nothing other than the “despotic inroads on the rights of property, and on the conditions of bourgeois production”[37] envisaged by Marx and Engels in The Communist Manifesto.

The old police force was abolished. The maintenance of public order was managed by the National Guard, the armed people, aided by police who were nothing more than responsible and revocable agents of the Commune. And what was the effect of this genuine “policing in the community”? Lissagary writes:

Her streets free during the day, are they less safe in the silence of the night? Since Paris has her own police crime has disappeared. Each one is left to his instincts, and where do you see debauchery victorious?[38]

The women of Paris, who had led the uprising on 18 March, were denied their right to vote in the elections of 26 March, one of the most obvious limitations of the Commune, which no doubt would have been overcome if it had survived for longer. But despite this, working women still took an equal share in the building and defence of workers’ power in Paris.

Working women played a key role in the Commune at all levels, as part of the neighbourhood Vigilance Committees, defending the barricades and participating in the armed fighting. Among them was teacher Louise Michel, who was elected as head of Montmartre Citizens Vigilance Committee. She fought as part of the National Guard both as a combatant as well as organising an ambulance service.

Working women set up their own organisations, such as theWomen’s Union for the Defence of Paris and for Aid to the Wounded, founded by a Russian member of the IWMA by the name of Elizabeth Dmitrieff, and also put forward their own demands, such as the abolition of “any competition between workers of different sexes, since, in the struggle they were waging against capitalism, their interests were identical”,[39] and the payment of equal wages for equal work. This demand was at least partially realised, with some women receiving four times as much as they had been paid by their old contractors. The abolition of night-work and the regulation of workplaces by the workers’ organisations also had an impact on the lives and conditions of working women. Education was to be taken out of the hands of the church and provided free to all children, regardless of sex or religion.

When one considers the context in which the Commune found itself, beset on all sides by enemies, still recovering from a siege, the achievements of the Commune are nothing short of miraculous. The experience of the Commune proved for all time that the working men and women of the world can run society democratically, without the need for bankers, landlords and industrialists. For this reason alone the Commune changed history. But attempting the transformation of society on this scale for the first time, and with a confused leadership, the Commune also made mistakes which it is our duty to learn from.

In his History, Lissagaray comments: “All serious rebels have commenced by seizing upon the sinews of the enemy – the treasury.”[40] And yet the Communards left both the treasury and the Bank of France untouched. When the revolutionaries took possession of the Ministry of Finance they discovered that the keys to the state coffers had been taken to Versailles – but they did not force the locks for fear that such a move would eliminate any prospect of a peaceful conciliation with Versailles. In fact, it was precisely this concession to Versailles that made conciliation less likely, as the Communards deprived themselves of a powerful lever with which to apply pressure on the enemy.

Likewise, the governor of the Bank of France had been so convinced that the revolutionaries would take possession of the bank that he fled before the Commune had even been elected, leaving three billion francs in cash, jewels and assets in the vaults. Without money to pay the National Guard, the Communards sent the great conciliator of the classes, Beslay, to negotiate. At his modest proposal that the Commune should appoint a new governor of the bank, the deputy governor, who had remained at the scene, protested vehemently and pleaded with him to save “the fortune of France”. So moved was the representative of the Commune that on his return to the Hôtel de Ville he explained the bank could not be touched because: “If you violate it, all its notes will be so much waste-paper.”[41]

The leadership of the Commune, accepting this excuse, then appointed Beslay as ‘delegate’ to the bank, which magnanimously agreed to give the Commune a loan of 400,000 francs a day. They did not even order the National Guard to occupy the building in case of sabotage. Of course, none of this prevented the bourgeois press from howling about the violation of public and private property, and of looting on a vast scale.

Another opportunity was missed inside the Hôtel de Ville itself, which contained official records and diplomatic papers dating back even to the Great Revolution. The Communards could have exposed the secret diplomacy, dirty deals and plots against the people carried on since the days of Napoleon I – but the Council neither published the vast bulk of the documents nor took possession of them as an important ‘hostage’ from the regime.

The leadership, itself leaderless, without a plan and unsure of whether it was to supplant the old power or supplement it, held itself back from the brink in the hope of preventing further bloodshed. Meanwhile, Thiers and the Versaillais were assembling an army, intent upon a war of extermination against the Parisian working class. On 2 April, four days after Paris celebrated the proclamation of the Commune, their artillery began to bombard the city.

Paris isolated

With a potential force of over 200,000 men in possession of the surrounding forts, and plenty of rifles and cannons, the Commune presented no easy target for the Versaillais. The constant shelling of the city, which killed many innocent civilians, was to no avail. The workers of Paris, including women and adolescents, were fighting for more than their lives – they felt they were fighting for the future of humanity. And they fought like lions.

For seven weeks, the Versaillais were prevented from even reaching Paris, let alone entering it. But even with its abundance of strength and courage, Paris could not hold out on its own forever. The fate of the revolution thus depended entirely on its ability to spread from Paris to the provincial towns and from there into the countryside, where the bulk of the peasantry remained loyal to the Versailles Assembly.

From the rising of 18 March up to as late as May, cities and towns all over France responded with messages of solidarity for Paris. In many important cities, the workers launched their own insurrections in support of the Commune, most notably Lyon, Marseilles and Toulouse. If these key centres of the South had fallen, the situation could have changed dramatically. Nor were these the only places in which risings took place: Creuzot, St. Etienne (an important mining city) and Limoges all briefly gave birth to their own Communes. Even in those places where the workers did not seize the Hôtel de Ville, there were anti-Versailles demonstrations, the flying of the red flag and other similar ‘disturbances’ all over France. In Bordeaux, the first seat of the reactionary Rural Assembly, the workers arrested several police officers and pelted stones at the infantry barracks shouting, “Vive Paris! Death to the traitors!”[42]

In his 1921 introduction to The Civil War in France, Trotsky, who had just carried out and successfully defended an insurrection himself, wrote the following:

If the centralised party of revolutionary action had been found at the head of the proletariat of France in September 1870, the whole history of France and with it the whole history of humanity would have taken another direction.[43]

The truth of this statement can be seen at many points in the history of the Paris Commune, but it is clearest of all in the failure of the revolution to successfully spread to the provinces.

As in Paris, the risings took place more or less spontaneously, and tended to bring to power leaders who were not prepared for the fight and lacked any direction from the centre of the revolution. This resulted in an extremely uneven pattern across the country and allowed each rising to be isolated and extinguished in turn. Many workers instinctively grasped the need for centralised direction and looked to Paris for a lead. The workers of Limoges even sent a delegate to Paris to request a “commissary”.[44] The members of the Council said they would consider it, but no one was sent.

As well as the provincial towns, there was the decisive question of the peasantry. As was seen in the elections of 8 February, the composition of France at this time was overwhelmingly peasant and rural, and this section of the population had been used many times by the ruling class as a means to keep the political struggle of the working class in check. However, it must not be forgotten that this was the same peasantry that had lit up the French countryside with the burning chateaux of their lords in August 1789. It would therefore be a mistake to assume that the peasantry can only ever be a tool of reaction.

The majority of French peasants viewed the revolution with suspicion and even hostility, which was fed by the torrent of false propaganda being poured out of Versailles. Fundamentally, however, the position of the average peasant was summed up in the question, “What does the republic give me to eat?” Only a programme linking the interests of the poorer peasants and agricultural labourers with the young workers’ republic in Paris, combined with the resolute determination of the workers to carry it out, could win a decisive section of the rural population to the red flag of the Commune. However, this programme never really emerged.

The Commune had released a declaration to the provinces, but only in very general terms, stating that “Paris fought for all France”. An address to the peasants had also been drafted, which explained:

Brother, you are being deceived. Our interests are the same. What I ask for, you wish it too… What Paris after all wants is the land for the peasant, the instrument for the workmen.[45]

This could have been the beginning of a serious campaign in the countryside, but without cadres or any form of organisation in the provinces the distribution of this important address was distributed by balloons, which dropped their cargo in random parts of the countryside.

Thiers, on the other hand, did everything he could to restrict the revolution to Paris. Met with protests against his vicious war against Paris, he replied, “Let the insurrection disarm; the Assembly cannot disarm. But Paris wants the Republic. The Republic exists; by my honour, so long as I am in power, it will not succumb.”[46] This promise was more than enough for the bourgeois Republicans in the Assembly to abandon Paris to its fate. Prominent Republican deputies were sent around the provinces to appeal for calm, while Paris was being bombarded. One such ‘friend’ of the Republic, Louis Blanc, explained that although Paris was right to defend the Republic, “the people who were there striving to seize the government were fanatics, fools, or rogues”,[47] weeping crocodile tears over the “hideous struggle”.

With the republican middle classes thus subdued, and with the peasantry still opposed to the revolution, the workers found themselves in a tiny minority. In the provincial towns, their revolts were put out one by one. In the meantime, Bismarck had released 60,000 prisoners of war in return for a king’s ransom. With the Versaillais army growing and able to focus its full strength on the capital, the position of the Communards became increasingly desperate.

Paris crushed

Since the beginning of their assault on 2 April, the Versaillais had been kept at bay by the heroic resistance of the workers. The women were especially famed for their unbreakable courage. One captured Communard warned the Versaillais, “Believe me, you cannot hold out; your wives are all in tears, and ours do not weep”,[48] in words reminiscent of the Spartan mothers who sent their sons off to fight with the words, “Come back with your shield, or on it.”

Many women volunteered to tend to the wounded. Dozens were killed, rushing into the thick of the fight in order to pick up a fallen comrade. Others took up rifles themselves and held forts and barricades against often desperate odds. So ferocious was the resistance of the women workers that one correspondent from The Times (the main daily newspaper of the English bourgeoisie at the time) remarked, “If the French nation were composed only of French women, what a terrible nation it would be!”[49]

The incredible heroism and self-sacrifice of the women should not come as a surprise. The working women of 1871 bore, and continue to bear, a double burden of oppression under capitalism. The working women therefore had even more to gain from the defence of the workers’ republic than the men. Both at the birth of the Commune and during its last agonising days, the working women fought and laboured for the future of all humanity.

After a bitter struggle, on 21 May the Versaillais entered Paris. What followed was seven more days of brutal street fighting, which became known as Bloody Week. In every district, the Communards erected barricades and forced the Versaillais to take the city street by street. Meanwhile, Versailles continued to bombard the city indiscriminately. Thiers even boasted in August 1871: “We have crushed a whole district of Paris.”[50]

Paris was transformed into a vision of hell. At night the city was lit up by the burning buildings while by day the sky was darkened by the smoke. The streets were filled with the thundering of the artillery and the screams of the dying. The pavements were covered in blood. Wherever they were victorious, the defenders of bourgeois ‘civilisation’ gave themselves over to slaughter and pillage. Captured Communards were lined up against a wall and shot on the spot. Even non-combatants who were suspected of supporting the Commune were executed without trial. Any shop owners who had supported the Commune had their establishments ransacked and were beaten without mercy. Women wearing ragged clothing, or carrying a pail, were shot as suspected petroleuses (arsonists). As many as 20,000 people were slaughtered in a single week.

At the news of the massacres being carried out by the Versaillais, the Communards threatened to execute seventy hostages, including the Archbishop of Paris. It should be noted that as early as 12 April and again on 14 May, the Commune had offered to exchange these hostages for just one man: Auguste Blanqui. But Thiers rejected their offer, not only because he suspected the value of Blanqui to the revolution, but also to use their lives as a pretext for the horrific reprisals he had already planned for the Parisian working class. On 24 May, in an act of desperation, the Communards executed the Archbishop and five other hostages. The responsibility for their deaths lies entirely at Versailles.

At last, the strength of the remaining defenders gave out, and the fighting ended on 28 May with the fall of the barricade at Rue de Ramponeau, in the working class stronghold of Belleville. In the Assembly, Thiers declared, “The cause of justice, order, humanity, and civilisation has triumphed”[51] to the cheering deputies. The champions of “justice, order, humanity and civilisation” then proceeded to arrest and execute thousands more suspected Communards.

In the name of “justice” many barristers refused to defend the accused, while many others actively worked with the prosecution. One man was sentenced to death, despite having nothing to do with the Commune, because “he was one of the leaders of the Socialist party” and so “one of those men, in short, of whom a prudent and wise Government must rid itself when it finds a legitimate occasion to do so”.[52]

In the name of “order” government troops shot passers-by for as much as wearing a watch. Corpses were searched and robbed. Even the conservative press complained: “These are no longer soldiers accomplishing a duty.”[53] In the chaos, many innocent people were denounced as Communards by personal or business rivals. The police received a total of 399,823 denunciations.[54]

In the name of “humanity” the government locked up thousands of men, women and children in squalid cells, devoid of light, air or food. The Versaillais themselves admitted to taking 38,568 prisoners, of whom 1,058 were women and 651 were children, including seventy-three under the age of fourteen. The youngest prisoner was seven years old.[55] Lissagaray estimates that 2,000 prisoners died due to the conditions.[56] Pregnant women were not spared the torture and many miscarried or gave birth to stillborn children. Many others went mad. “Human life has become so cheap, that a man is shot more readily than a dog”,[57] wrote The Times.

In the name of “civilisation”, so many were massacred that there were not enough carts to take away the bodies. The dead piled up in the streets. In June even the bourgeois press began to plead, “Let us not kill any more”, not because of any sympathy for the victims, but because the stench and disease from the rotting corpses threatened to consume the whole city. Amongst these scenes, reminiscent of the height of the Black Death, bourgeois Paris celebrated its return with a festival of debauchery in the cafés, the brothels and the streets. Even the pro-Versailles press complained, with one correspondent quoting Tacitus:

Yet on the morrow of that horrible struggle, even before it was completely over, Rome, degraded and corrupt, began once more to wallow in the voluptuous slough which was destroying its body and polluting its soul – alibi proelia et vulnera, alibi balnea popinaeque (here fights and wounds, there baths and restaurants).[58]

The total number of people killed by the Versaillais during Bloody Week and the reprisals that followed was estimated at 30,000. In addition, more than 13,000 were transported to New Caledonia, their families left destitute. Many more were forced to flee the country. In the by-elections of July, Paris had 100,000 fewer electors than on 8 February.[59] This was not an accident or an unintended ‘excess’ in the heat of the struggle. Even before 18 March, Clément-Thomas spoke of “finishing off la fine fleur [the cream] of the Paris canaille [scoundrels]”.[60]

It was necessary in the eyes of the French ruling class to exterminate the most advanced section of the proletariat, the living memory of the struggles of 1848 and 1871. This social peace was bought even at the expense of the short-term economic interests of the bourgeoisie. In October 1871, an official report claimed that certain industries were having to refuse orders due to a lack of workers.

The Commune’s legacy

The Third Republic, which had been brought into being by the Parisian workers, was cemented with their blood. At the top of the hill of Montmartre, the birthplace of the Commune, the bourgeois built the Sacré-Cœur Basilica as a ‘penance’ not for the thousands of men, women and children slain by Versailles, but for the ‘crimes’ of the Commune. Today it still stands as a monument to the stinking hypocrisy of the French ruling class.

For their part, the fallen Communards are remembered in a quiet and secluded corner of the Père Lachaise cemetery, where some of the last defenders of the Commune were captured and shot. But in truth the Paris Commune does not require any statues or monuments. The real monument to the Commune lives in the revolutionary struggle for socialism, to which it made a titanic and indelible contribution.

The experience of the Commune made a huge impression on the ideas of Marx and Engels who, throughout their lives, distilled and updated their revolutionary programme on the basis of the struggles, the victories and defeats, of the working class. In 1872, Marx and Engels wrote in their preface to a new German edition of The Communist Manifesto that the programme of demands contained in part II of the Manifesto would have been “differently worded today”, particularly “in view of the practical experience gained, first in the February Revolution [of 1848], and then, still more, in the Paris Commune, where the proletariat for the first time held political power for two whole months”.[61]

Specifically, what the Commune proved was that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes”.[62] The importance of this statement can clearly be seen from the fact that Marx and Engels thought it necessary to effectively correct and update The Communist Manifesto on this basis. Rather than trying to use the existing parliament, army, bureaucracy etc., which had evolved under bourgeois society, the workers would have to smash this “state parasite”[63] by revolutionary means and replace it with their own political organisation, one in which “the more the functions of state power are performed by the people as a whole, the less need there is for the existence of this power”,[64] as Lenin put it, based on his own study of the Commune and Marx’s Civil War in France.

The impact of the Commune was not confined to the realm of theory either. In September 1871 the International Workingmen’s Association held a Congress in London, which was attended by survivors of the Commune, including Blanquists who had been won over to the International. At this Congress the lessons of the Commune and its defeat were discussed at length, leading to the passing of the following resolution, the final form of which was drafted by Marx:

Considering, that against this collective power of the propertied classes the working class cannot act, as a class, except by constituting itself into a political party, distinct from, and opposed to, all old parties formed by the propertied classes;

That this constitution of the working class into a political party is indispensable in order to ensure the triumph of the social revolution and its ultimate end – the abolition of classes;

That the combination of forces which the working class has already effected by its economical struggles ought at the same time to serve as a lever for its struggles against the political power of landlords and capitalists –

The Conference recalls to the members of the International:

That in the militant state of the working class, its economical movement and its political action are indissolubly united.[65]

This was a decisive blow against the Bakuninist and Proudhonist tendencies within the International, who preached abstention from politics and the struggle for state power. In effect, the Commune clarified not only the end goal of the workers’ struggle but the means by which it was to be achieved, thus shaping Marxism itself in the process. It has been said that the Marxist programme is nothing other than the generalised experience of the working class. The truth of this statement can be seen in the fact that every one of the fundamental points of this programme – the need for the political independence of the working class and a centralised workers’ party, the international character of the workers’ struggle, and the need to smash the bourgeois state, replacing it with the dictatorship of the proletariat – were forged and tempered in the rise and fall of the Commune.

The workers of Paris had shown the way. They proved in only two months that a new world was possible. The red flag of the Commune was raised as the banner of the world working class and The Internationale, written a month after the fall of the Commune, became its anthem. And the lessons of the Commune, distilled and preserved in The Civil War in France and other writings, have served to educate and inspire millions of revolutionaries, not least Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

Today, as the decay of the capitalist system offers horrors surpassing even the worst crimes of the Second Empire, a rising generation of workers is again taking up the fight for the emancipation of humanity. It is our duty to study the Commune, its triumphs and its mistakes, and to put those lessons into action. If we do this with even half of the heroism of the Communards, we cannot fail.

Vive la Commune!

Originally published on Socialist.net

Notes

[1] K. Marx, Marx and Engels Collected Works (Henceforth referred to as MECW), Vol. 11, Lawrence & Wishart, 2010, p. 112.

[2] Ibid., p. 143.

[3] K. Marx, The Civil War in France, Wellred Books, 2021, p. 3.

[4] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, International Publishing Co., New York, 1898, p. 11.

[5] Ibid., p. 12.

[6] K. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 17.

[7] L. Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, Haymarket Books, 2008, p. XVII.

[8] K. Marx, ‘Letter to De Paepe, 14 September 1870’, MECW, Vol. 44, p. 80.

[9] F. Engels, ‘Introduction to the 1891 Edition’ in K. Marx, The Civil War in France, Wellred Books, 2021, p. LXVI.

[10] K. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 18.

[11] Ibid., p. 18.

[12] Ibid., pp. 17-18.

[13] K. Marx, ‘Letter to Kugelmann, 4 February 1871’, MECW, Vol. 44, p. 108.

[14] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p.15.

[15] Ibid., p.16.

[16] Ibid., p. 22.

[17] Ibid., p. 23.

[18] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 26.

[19] Ibid., p. 32.

[20] “Affiche rouge”: Au peuple de Paris, les délégués de vingt arrondissements de Paris, FICEDL.

[21] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 57.

[22] Ibid., p. 75.

[23] Ibid., p. 62.

[24] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 69.

[25] Ibid., p. 76.

[26] Ibid., p. 79.

[27] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 79.

[28] K. Marx, ‘Letter to Kugelmann, 12 April 1871’, MECW, Vol. 44, p. 132.

[29] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 90.

[30] Ibid., p. 92.

[31] V. I. Lenin, ‘Discussion on Self-determination Summed Up’, Selected Works, Vol. 5, Lawrence & Wishart, 1953, p. 303.

[32] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 156.

[33] V. I. Lenin, State and Revolution, Wellred Books, 2019, p. 45.

[34] K. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 48.

[35] Ibid., p. 48.

[36] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, pp. 232-233.

[37] K. Marx and F. Engels, The Communist Manifesto, in The Classics of Marxism: Volume One, Wellred Books, 2013, p. 22.

[38] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 302.

[39] E. Thomas, The Women Incendiaries, Secker & Warburg, 1967, pp. 45-46.

[40] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 187.

[41] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 188.

[42] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 273.

[43] L. Trotsky, ‘Lessons of the Paris Commune’, in K. Marx, The Civil War in France, Wellred Books, 2021, p. XLIX.

[44] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 180.

[45] Ibid., p. 228.

[46] Ibid., p. 196.

[47] Ibid., p. 274.

[48] Ibid., p. 208.

[49] The Times, 29 May 1871, quoted in P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 397n.

[50] “Nous avons écrasé tout un quartier de Paris” – Ibid., p. 254.

[51] “La cause de la justice, de l’ordre, de l’humanité, de la civilisation, a triomphé.” – Ibid., p. 395.

[52] Echo de la Dordogne, 19 June 1871, quoted in P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 493.

[53] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 348.

[54] Ibid., p. 402.

[55] Ibid., p. 404.

[56] Ibid., p. 411.

[57] The Times, May-June 1871, quoted in E. Marx’s introduction to P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. VII.

[58] P. O. Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, p. 487.

[59] Ibid., p, 404.

[60] K. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 35.

[61] K. Marx and F. Engels, The Communist Manifesto, Penguin Books, 2002, p.194.

[62] Ibid. p.194

[63] K. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 47.

[64] V. I. Lenin, State and Revolution, p. 43.

[65] ‘Resolution of the London Conference on Working Class Political Action’, September 1871. Available online from the Marxists Internet Archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/09/politics-resolution.htm (accessed 12 March 2021).